Reading time: Around 7 minutes.

–> Lire la version française de cet article ![]()

Some time ago (in April 2022), I had the pleasure of listening to a literary encounter with Rokhaya Diallo, whose work on the Kiffe ta Race podcast I particularly enjoy. Among those present, several spoke about colorism, an important issue in our society. Where racism legally distinguished whites from blacks in the Caribbean in the 18th century, colorism led to systemic hierarchization and discrimination based on variations in the intensity of people’s skin color; in other words, within a community of non-white people, the darker-skinned individual was devalued and further discriminated against compared to the lighter-skinned one. One of the people asked what could be done to fight against this phenomenon, which is particularly internalized in our islands; in the absence of ready-made solutions, I can at least explain how it was historically constructed in the Caribbean and what it implied in the past, to better understand how it can still be active. Today, I’m going to establish the framework, and talk about how Caribbean societies have been forged over several centuries around the notion of « color », leaving deep and traumatic traces for the men and women concerned right up to the present day(*).

As I’ve already written elsewhere for a series of articles on the prejudice of color « throughout my posts I will talk about Blacks (unless I specify otherwise, I will talk about Blacks whether they are of mixed race or not), they were the numerical majority of people in the Caribbean islands, Africans or their Creole descendants; for the most part, they were reduced to the status of slaves in the 18th century. I will talk about their counterpart: the Whites, whether they were Western/European or Creole, on the eve of the French Revolution they formed less than 20% of the islands’ population, but were the oppressors in the service of their colonial project. Finally, I am going to talk about the Free People of Colour to evoke in particular those who, whether black or of mixed race, freed or their descendants, were legally free.

Colonialism, slavery and racism in the France of the Enlightenment!

To understand how colorism took shape, I’m going to look back at some fundamental elements in the construction of Caribbean societies during the colonial period. The colonial project of the Kingdom of France aimed to enrich the country through the exploitation of land for the production of export crops (tobacco, sugar cane, cocoa, coffee, cotton…); to realize this colonial project, France, like other European nations of the time, relied on the exploitation of enslaved labor from the transatlantic slave trade. Thus, colonial society in the Caribbean was initially based on a binary vision, with the white man as master and the black man as slave.

In practice, various situations were possible. In the early days of colonization, not only were some enslaved people freed (though not many), but relations between white and black people (more undergone than consented to) led to « miscegenation »(**) within the population. As the exploitation of the colonies was mainly based on enslaving black people, a whole system of segregation and discrimination of non-white people was put in place to maintain the established order ideologically desired by the European colonists: this is color prejudice. This racist legal and social system, whose mechanisms I developed in the above-mentioned series of posts, led to the existence of a tripartite society, where, between the free white people and the black people reduced to slave status, were the free people of color.

Expressing skin color and mixed race in the 18th century

Before clarifying what colorism implies, I’d like to lay the foundations of the vocabulary used at the time to evoke the supposed generation of mixed race and/or people’s phenotype. I’d also like to come back to the conceptual tool I’m using to talk about it while trying to extricate myself from it… always an imperfect balancing act. I’m going to use Martinique as a case study, since that’s where I do my research.

In the 17th century, in the early days of colonization in Martinique, the only terms used to distinguish people on the basis of skin color were « white » [blanc], « black »[noir] and « mulatto »[mulâtre] in everyday sources (notably parish registers). The designation « mulatto » then characterized the offspring of the union of a « negress »[négresse] and a « white » or of two people themselves perceived as « mulatto », and also more generically any person of mixed race. Then, in the 18th century, as the population of free people of color grew, an ethno-racial categorization developed through a whole vocabulary to continue stigmatizing people with non-white ancestors, even though their skin tone sometimes no longer distinguished them from Whites due to successive generations of interracial relationship. Thus, a person was called a « mestive » if he or she was born of a « mulattress » and a « white », a « quarteronne » if he or she was born of a « mestive » and a « white », and a « malelouque » if he or she was born of a « quarteronne » and a « white ». On the other hand, there was only one level for defining a person born from a « nègre » or « négresse » and a « mulâtre » or « mulâtresse », referred to as a « cabresse » or « capresse ».

This vocabulary differs from island to island and from period to period, but equivalent mechanisms – involving the desire to describe the body and/or the generation of supposed « miscegenation » – can be found throughout the Caribbean. Historian Jean-Pierre Sainton has developed a conceptual tool for studying and comparing these different territories. He has defined a typology to bring together all existing terminological variations into four categories. These are:

- non-mixed black people « nèg nwé » (in the documents: « noir », « nègre », « negrillon »…), people perceived as being black and reflecting the absence of « miscegenation »,

- mixed-race black people « nègres métissés » (« cabre », « câpre », « capresse »…), people whose phenotype showed some signs of mixing with white individuals while mainly reminding the attributes of people perceived as black,

- « mulatto » people (« mulâtresse », « mule »…): this category was intended as the expression of « miscegenation » between white and black people, and was often used as a catch-all category to designate « miscegenation » in a more generic way,

- light mixed-race people « mixed-blood and light mixed-race » (« mestif », « métive », « quarteron », « mamelouque »…) people whose phenotype showed mixed-race traits mainly reminding the attributes of people perceived as white,

I know it’s a lot of periphrasis, but these expressions allow us to compare the situation in different territories, and I’m not comfortable with the systematic reuse of historically charged words; that’s the best I can come up with at the moment. Keep these 4 ethno-racial categories in mind, because I’m going to use them to analyze data illustrating the construction of colorism.

If some of you are wondering why there’s this dissymmetry in vocabulary – why don’t I talk about « mixed-race white people » rather than « light mixed-race people »? – well, because at the time, the idea was precisely to maintain an impassable line of separation between whites and others, which is why I also sometimes use the term « non-white » to evoke this construction of alterity that consisted in inferiorizing all those who were excluded from the « white » category.

You may also have noticed that I always refer to a white, as a man, in the preceding lines for the aforementioned « light » mixed races, whereas I refer to both men and women for mixed-raced black people. This is no random occurrence. The archives show that it was essentially relationships between white men and non-white women that gave rise to the « miscegenation » of the population. The control of white women’s sexuality and the social taboo that existed on the subject made mention of their relationships with black men rare in the colonies (and particularly in Martinique!), even if there must have been a few, perhaps followed by the abandonment of the child or the expulsion of the « offending » woman from the island, or worse.

What needs to be understood here is the composition of the two non-white groups: enslaved and free people of color. Whether black people were mixed-race or not, they could be of free or slave status. A light-colored mixed-race person could be a enslaved person (as in the case of Emile, « mestive »), just as a non-black mixed-race person could be free (as in the case of Marie Catherine Alerte, « négresse »). However, while skin color did not strictly condition the status of individuals, studies on the subject show that there was a correlation between skin color and people’s life opportunities. That’s the burden of colorism! In the next few posts, I’ll be commenting on these assertions in particular.

-

- A light-skinned enslaved person was more likely to be emancipated.

- A light-skinned enslaved person was more likely to have a trade or skilled activity.

- A light-skinned enslaved person had a higher market value.

- A light-skinned free person of color had more opportunity to pass.

- A light-skinned free person of color had more opportunity to receive an education or to own property.

(**) Update 07/26/2023: Following the discussion with Patty (see comments section), I’ve tried to improve the translation, putting the word miscegenation in quotation marks to recall its negative charge, or substituting the term with a close expression (interracial relationship) when this didn’t require reshaping the sentence structure.

(*) If you’re one of those people tempted to comment loud and clear that they don’t see the color of others, because « we’re all the same », I’d ask you to please focus on the fact that I’m not discussing your personal perception here, but am interested in how a society has been forged over several centuries. Even if you don’t find them insulting or offensive, comments of this kind will be deleted to give a break to readers who, like me, are exhausted by the regular rejection or denial of their experiences and feelings (or even of the results of scientific work on the subject), and who have no choice but to deal with the still perceptible consequences of this violent history on a daily basis.

All articles of the series Colorism and life opportunities during Slavery

#1 Skin color and mixed race in the 18th century

#2 Differentiated access to freedom

#3 Inequality of opportunities at work

#4 Values tainted by prejudice

#5 The imbalance in relations

#6 Capital disparity

French Bibliography

- Pierre-Louis, Jessica. « La couleur de l’autre L’altérité au travers des mots dans les sociétés coloniales françaises du Nouveau Monde (XVII-XVIIIe siècle) ». In Poétique et Politique de l’altérité Colonialisme, esclavagisme, exotisme (xviiie-xxie siècles), 143‑54. Le dix-huitième siècle, n° 31 in Rencontres. Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2019.

- Sainton, Jean-Pierre. Couleur et société en contexte post-esclavagiste: la Guadeloupe à la fin du XIXe siècle. Pointe-à-Pitre: Jasor, 2009.

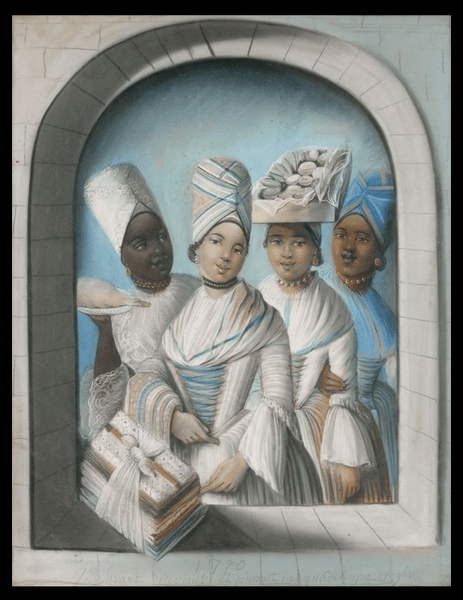

Iconography

- Base de données Joconde

SAVART Marie Joseph Hyacinthe, Les Femmes créoles (titre factice), [1770], M1061000003

Hi, thanks, this was so interesting. There’s a lot I could try to comment on, but will restrict myself to the sense of unease I felt reading the word miscegenation in this article. I’d be interested in hearing – in french or English – why you chose this word, that to me is charged with racist meaning

J’aimeJ’aime

Bonjour Patty,

J’ai utilisé le mot miscegenation, car c’est habituellement celui que je retrouve dans la littérature pour parler de métissage (je l’ai déjà vu, mais plus rarement, dans sa forme française miscégénation), le mot crossbreding me semble davantage s’appliquer aux animaux. Je comprends parfaitement l’inconfort, je le ressens d’autant plus souvent moi-même que je n’ai pas suffisamment de maîtrise de la langue anglaise pour mesurer la charge de tous les mots qui rentrent dans ce champ d’étude (et ils sont si nombreux! La question se pose d’ailleurs aussi en français parfois), l’évolution de cette charge (je pense par exemple à l’expression free colored qui a longtemps été employée pour parler des personnes libres de couleur dans la recherche et à laquelle on préfère actuellement free people of color justement à cause de la charge raciste/négative du premier) ou encore la perception selon la position de celui/celle qui parle (certains collègues sont à l’aise et légitimes avec le fait de parler des « nègres » et de s’autodésigner comme tel, mot que je ne me sentirai pas autorisée à utiliser de même)… Je crains donc d’employer un vocabulaire méprisant par défaut de connaissance. Je suis ouverte à des propositions recouvrant le même concept si vous pensiez à un autre mot en particulier.

J’aimeAimé par 1 personne

Hi again, it’s all a fascinating minefield, what language to use to address subjects that are so laden with cruelty as our recent history of European colonialism and enslavement. Cross breeding sounds even worse than miscegenation, but that word is pretty bad, really invented in order to criminalize interracial sexual relations. By the way, your mastery of English is pretty great. I always read your articles in both languages, enjoying the subtle differences.

J’aimeJ’aime

Un champ de mines en effet, mais qui a le mérite de nous obliger à réfléchir au choix de nos mots (et à l’histoire de leur existence). Comme noté dans la mise à jour, j’ai essayé de trouver une solution plus acceptable de traduction pour ce billet (usage des guillemets). Dans les prochains billets, à défaut d’avoir une traduction littérale neutre du mot métissage, j’essaierai de trouver en amont des formulations qui évitent autant que possible la nécessité de recourir à son équivalent anglais.

J’aimeJ’aime