Reading time: Around 5 minutes.

–> Lire la version française de cet article ![]()

What difference did it make in one’s life to be a free or enslaved non-mixed black, mixed-race black, « mulatto » or light mixed-race person in the Caribbean in the 18th century?

In the first post, I explained the context in which colorism developed, in other words, a colonialist context based on slavery, from which emerged color prejudice, a racist system that segregated and discriminated against black people. I’ve also clarified the words I’m going to use to analyze the impact of colorism on life opportunities.

In posts 2, 3 and 4, I take a closer look at the impact of colorism on people reduced to the status of slaves. I approach this from a statistical angle, which sometimes makes things a little indigestible to read (the statistical passages are shifted to the margins), but it also serves as a reminder that we’re not talking about an anecdotal phenomenon. The prevalence of colorism is measurable in 18th-century society.

This week, we continue our series on colorism with episode 4. I analyze the influence of colorism in estimating the value of enslaved people.

Values tainted by prejudice : when an enslaved person’s skin was lighter, the market value increased.

In the « Esclavage en Martinique » database, the 10254 enslaved people valued financially were valued on average at around 1581 livres. This price varied according to several factors, including gender, but even more so according to age, state of health and, as we saw in the previous post, skills.

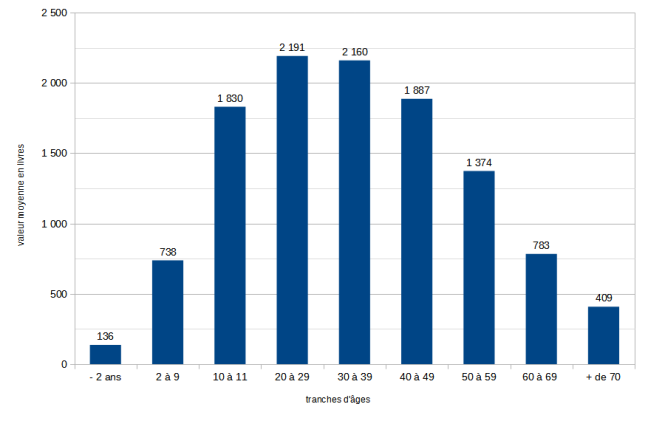

In the « Esclavage en Martinique » database, women were valued at an average of 1506 livres, while men were valued at 1662 livres. Health status is another important indicator. People who were reported as having an injury, illness or worn-out body were valued at an average of just 1082 livres, while those who were not were valued at an average of 1608 livres. Skills are another important indicator; the 802 people who provided information on their trade were valued at an average of 2273 livres, the other 9452 at 1522 livres. Finally, age was another important factor in determining prices. Young children were poorly valued (due to their non-productivity and high mortality rate). A child between the ages of 2 and 9 was priced at an average of 738 pounds. On the other hand, as the prime working age was between 20 and 40, the highest averages were observed: enslaved people in this age category were valued at an average of 2177 pounds. The average value then fell progressively, dropping below 1,000 livres for those over 60.

Graph showing the estimated average value of enslaved persons by age group in the « Esclavage en Martinique » database.

Finally, I made calculations to see whether skin tone and phenotype contributed to the value of enslaved people independently of the other criteria. To do this, I tried to erase as far as possible the effects of the other parameters that had a strong influence on the estimate: skills, state of health and age. I have reproduced my calculation table in full, but only the figures in bold can be analyzed; for the others, the statistical sample is once again too small. Nevertheless, it shows several interesting things. Firstly, you can see how the value of individuals evolved with their age: lowest when young, peaking between the ages of 20 and 40, before starting to fall again as they age.

Table showing the average value of enslaved women and men according to age and ethno-racial categorization in the Esclavage en Martinique database (gross number of people and average value in pounds), excluding those with a skill and those with an indication of their health.

| Nnon-mixed blacks | Mixed-race blacks | « Mulattoes » | Light mixed-race | |||||

| – de 10 |

378 | 634L | 65 | 710L | 149 | 713L | 43 | 564L |

| 10 – 19 | 532 | 1839L | 56 | 1865L | 143 | 1904L | 17 | 1701L |

| 20 – 29 | 491 | 2159L | 30 | 2280L | 65 | 2303L | 5 | 2390L |

| 30 – 39 | 337 | 2106L | 12 | 2217L | 34 | 2360L | 4 | 2775L |

| 40 – 49 | 196 | 1810L | 5 | 1860L | 25 | 2096L | 2 | 1510L |

| 50 – 59 | 114 | 1273L | 2 | 850L | 8 | 1638L | 0 | |

| + de 60 |

108 | 633L | 1 | 400L | 7 | 716L | 0 | |

| All ages combined | 2925 | 1632L | 209 | 1483L | 541 | 1629L | 87 | 1161L |

I selected the 3762 people who were estimated, but had no indication of health status or skills, and looked at the average values by age bracket (in 10-year increments) to consider the greater probabilities of emancipation for lighter-skin people. Looking at the « all ages » line, there is no strict correlation between skin color and value assigned. The 2925 non-mixed black people were valued on average at 1632 livres ; this is almost equivalent to the 541 « mulattoes » people valued on average at 1629 livres. However, if you focus on the only two comparable age groups (under 10 and 10-19), you can see that there is indeed a difference in valuation between the two categories distinguishing mixed-race people.

Ethno-racial category was not the main factor in estimating the value of enslaved people, but the results show that it did influence the value attributed to them, to the detriment of darker skins.

How can we explain the fact that, on average, people perceived as non-mixed black were less well estimated?

On this point, I think two elements may contribute. In the case of mixed-race children who were not the offspring of their own masters, the latter may have been calculating purely material gain from a possible resale to the child’s father. But more than that, I think we need to see in this intrinsic difference given to the phenotype, the manifestation of the social anchoring of color prejudice. Indeed, the 1777 memoir stated: « one cannot put too much distance between the two species; one cannot imbue negroes with too much respect for those to whom they are enslaved. This distinction, rigorously observed even after freedom, is the principal bond of the slave’s subordination, through the resulting opinion that its color is doomed to servitude and that nothing can make it equal to its master. The administration must be careful to strictly maintain this distance and respect ». [on ne saurait mettre trop de distance entre les deux espèces ; on ne saurait imprimer aux nègres trop de respect pour ceux auxquels ils sont asservis. Cette distinction, rigoureusement observée même après la liberté, est le principal lien de la subordination de l’esclave, par l’opinion qui en résulte, que sa couleur est vouée à la servitude et que rien ne peut la rendre égale à son maître. L’administration doit être attentive à maintenir sévèrement cette distance et ce respect. ]Giving more value to lighter skins was an illustration of the impregnation of this idea in colonial society.

All articles of the series Colorism and life opportunities during Slavery

#1 Skin color and mixed race in the 18th century

#2 Differentiated access to freedom

#3 Inequality of opportunities at work

#4 Values tainted by prejudice

#5 The imbalance in relations

#6 Capital disparity

French Bibliography

- Pierre-Louis, Jessica. Les Libres de couleur face au préjugé : franchir la barrière de couleur à la Martinique aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, thèse de doctorat d’Histoire, AIHP-GEODE EA 929, juin 2015 à l’U.A.G.

- Régent, Frédéric. « Couleur, statut juridique et niveau social à Basse-Terre (Guadeloupe) à la fin de l’Ancien Régime (1789- 1792)». In Paradoxes du métissage, édité par Jean-Luc Bonniol, 41‑50. Paris: Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques – CTHS, 2001

Archives

- Manioc, la base de données « Esclavage en Martinique ».

- Durand-Molard, Code de la Martinique, op. cit., Ibid., n°34, 24 octobre 1713, arrêt conseil d’État concernant la liberté des esclaves; n°517, 7 mars 1777 mémoire roi pour servir d’Instructions au Sieur Marquis de Bouillé, Maréchal de Camp, Gouverneur de la Martinique, et au Sieur Président de Tascher, Intendant de la même Colonie.

Iconography

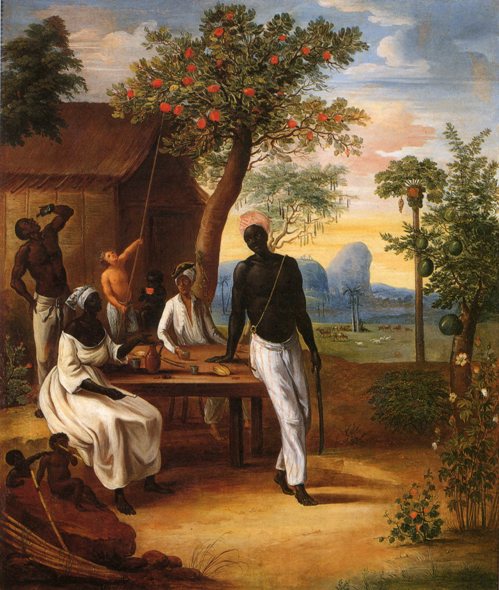

- Le Masurier, Esclaves noirs à la Martinique, 1775