Reading time: Around 9 minutes.

–> Lire la version française de cet article ![]()

What difference did it make in one’s life to be a free or enslaved non-mixed black, mixed-race black, « mulatto » or light mixed-race person in the Caribbean in the 18th century?

In the first post, I explained the context in which colorism developed, in other words, a colonialist context based on slavery, from which emerged color prejudice, a racist system that segregated and discriminated against black people. I’ve also clarified the words I’m going to use to analyze the impact of colorism on life opportunities.

In posts 2, 3 and 4, I took a closer look at the impact of colorism on people reduced to the status of slaves. This time, in posts 5 and 6, I focus on the repercussions of colorism on free people of color. I approach this from a statistical angle, which sometimes makes things a little indigestible to read (the statistical passages are shifted to the margins), but it also serves as a reminder that we’re not talking about an anecdotal phenomenon. The prevalence of colorism is measurable in 18th-century society.

This week, we finish the series on colorism with episode 6, in which I look at the ability to sign and the property, which amounts to a broader discussion of economic and cultural capital; finally, to conclude the series, I offer a brief reflection on the long-term impact of colorism.

The ability to sign: when a free person of color was lighter-skinned, he or she had more opportunities to receive an education.

The ability to sign registers is the most immediately accessible indicator of the educational level of the free population in the 18th century. However, knowing how to sign one’s name does not necessarily mean mastering the processes of reading and writing. In other words, what we measure with certainty is not so much competence as its absence!

Table of capacity or not to sign the act by husbands and wives at the time of their marriage in the parish registers.

| Non-mixed black | Mixed-race black | « mulattoes » | Light mixed-race | |||||

| Can’t sign | 98 | 73 % | 15 | 56 % | 155 | 64 % | 52 | 49 % |

| Can sign | 37 | 27 % | 12 | 44 % | 89 | 36 % | 55 | 51 % |

| All | 135 | 100 % | 27 | 100 % | 244 | 100 % | 107 | 100 % |

In my thesis database, between 1763 and 1793, the percentage of free men and women of color unable to sign at the time of their marriage is around 62%. Men were better educated than women. On average, 55% of free men of color can’t sign, compared with 69% of women. However, in order to have statistically acceptable samples, I’m not going to make gender distinctions within ethno-racial categories.

Looking at ethno-racial categorization, the table shows that 73% of non-mixed black people are unable to sign the register at the time of their marriage, while this number drops to 64% for « mulattoes » people and 49% for light mixed-race people. The « mixed-race black » column cannot be analyzed due to the small sample size.

The results obtained with my database are similar to those observed by historian Frédéric Régent. On average, the lighter-skinned people were, the more likely they were to learn to read and write.

Having property : when a free person of color was light-skinned, the better off he or she was financially.

Although there were disparities within each category, there was a strong correlation between economic capital and skin color. Not only were non-miwed black people in a minority to appear as property owners in notarial deeds, but they also had the most modest assets.

I have selected 122 patrimonies from notarial deeds for which I have an estimate of the property owned in colonial livre and an ethnic categorization of the person in the second half of the 18th century. While the average property owned by free people of color amounted to 9751 livres, non-mixed black people owned a patrimony valued on average at 5121 livres, mixed-race black people at 8225 livres, « mulattoes » at 9051 livres, light mixed-race people at 12336 livres.

I also calculated the medians, which provide information on the distribution of wealth. The median was 2841 livres for non-mixed black people, i.e. in my sample as many people in this category had wealth valued at less than 2841 livres as had wealth valued at more than this sum. For all other groups, the median ranged from 6930 to 7599 livres. The overall median was 6895 livres.

On average, the lighter-skinned a person was, the more financial assets they had.

How can we explain the fact that people perceived as non-mixed black were on average less well endowed with economic, social and cultural capital?

Historian Anne Pérotin-Dumon observes that, among free women of color, unmarried « mères-souches » [stem-mother] (as she calls them) participated in the social advancement of the next generations by trying to endow their children with an education and even modest property (by donation, for example) to facilitate their access to a good legitimate marriage later on. As we saw in the previous post, in colonial society, free women of color had every interest in choosing a lighter partner, or one of the same skin tone, to enhance or at least maintain the benefits of light skin. Just as a white father might be more inclined to emancipate his mixed-race offspring from slave status, he might also be more inclined to facilitate access to even the most elementary education, or to provide his free children with a small piece of land (even going so far as to circumvent regulations through fictitious sales and the use of trusts personn, as was the case with my ancestors’ land in the 19th century). The presence of a white ancestor thus favored the constitution of economic, social and cultural capital.

When a master freed a slave, he had to make sure that the freed person was able to support himself (through a skilled activity, for example) or he had to take care of him (young child, old man…); nevertheless, for non-mixed black people freed without a filial bond, the former master didn’t necessarily have a personal attachment as he did for his children. Non-mixed black people therefore had to be more self-reliant to ensure their needs.

Colorism: internalizing endured racism

In a society built on the exploitation of black bodies, the idea of a hierarchy of races opposing whites and blacks also led to a hierarchy in the shades of color, as demonstrated by the different estimates of the value of enslaved people, for whom darker skins were the most devalued.

Having a white parent or ancestor was a factor of freedom for the enslaved, a factor of social and economic advancement for the free people of color. Non-mixed black people had fewer opportunities for emancipation, which is why there was a clear difference between the composition of enslaved and free people of color in the 18th century. The majority of slaves were non-mixed black people, while the majority of free people of color were « mulattoes » or light mixed-race people.

The horizon of activities and qualifications available to non-Miscegenated black people was considerably limited, and, for the vast majority, confined to the fields, growing and processing agricultural produce. Enslaved light-skinned people had more opportunities to acquire a trade or skills that would take them out of the world of plantation, and it was the majority of activities that could be monetized in towns or cities that were then found among free people of color.

As a result, non-mixed blacks had less access to basic education and land ownership than lighter-skinned people.

Free black men were particularly limited by social organization when it came to finding a partner and starting a legitimate family. Free black women were more able to call upon their agentivity in this mater, and to using whitening and passing strategies in an attempt to improve the situation of their offspring and their daily lives. However, to do so, they had to give up the honor of a marriage for themselves in a society that stigmatized illegitimate births. And, for passing, in order to function, they had to choose their network of acquaintances carefully, which meant consciously or unconsciously renouncing sociabilities that were too reminiscent of their servile origins.

All this is just a statistical average; there are always examples of non-mixed-race people who have « made it » and, on the contrary, light mixed-race people who remained at the bottom of the social ladder all their lives in the 18th century. But they are the exception to the rule.

In addition to the traumatic psychological impact of racism and colorism on black people’s self-perception, these few cumulative opportunities over a lifetime (more opportunities to be skilled, to be emancipated, to have access to education, to own property…) have led to widening gaps over successive generations between black people.

Just like the negative perception of black people and color prejudice, these opportunities led those whose lighter skin set them apart to turn their attention and their hopes towards the dominant, white class, to value what brought them closer to the white and further away from the black. True, the white class denied them equality in freedom, but these people could at least rely on this skin to improve their situation. These opportunities played a part in anchoring the idea that the darker the skin, the more it was synonymous with failure, while, on the other hand, whiteness seemed to promise success, a model to aspire to.

With the legal repeal of color prejudice in the 1830s and the abolition of slavery in 1848, colorism, like racism, did not disappear. Both individually and collectively, colorism favored the economic and social emergence of the lightest-skinned non-whites persons, who formed the 18th-century colored elite, the bourgeoisie and the « great mulattoes » of the 19th and 20th centuries. Skin color has remained one of the principal means of defining a person’s social position.

In his Frech book Couleur et société en contexte post-esclavagiste, La Guadeloupe à la fin du XIXe siècle*, historian Jean-Pierre Sainton shows how mental representations of color led to the elaboration of identity processes, « i.e. mechanisms by which individuals represent, name, recognize, distinguish or aggregate themselves. » (p. 31) in relation to others. He has surveyed the richness of the contemporary lexicon of color, highlighting the differences in registers: pejorative for words surrounding the term « nègre » [negro] (charbon [coal], gwo siwo [molasses], goudron [tar]…), more flattering for those describing the skin of people of mixed race (light, sapodilla, cinnamom…). The same applies to hair texture. And, beyond the simple description of physical appearance, there are also a host of words that use the word « negro » to describe an individual’s behavior or situation in a negative way. In view of the social construction of the Caribbean, it’s not surprising that what he describes as the « complex negro » (internalization of negative stereotypes, fatality of the condition, social progress perceived as consisting in escaping one’s black condition) or the « malaise of mulatto » (ambivalent situation, weight of the presumption of betrayal) should be expressed.

Finally, the links between skin color and life opportunities of yesteryear have traced the lines of internalized contempt for our present beings. These expressions « la peau sauvée » [saved-skin], « chapé-couli »[escaped-coolie], « bel chivé »[beautiful air]… that we use to evoke our bodies and often disqualify the features perceived as « black », these sentences uttered without consciously weighing their full impact « I’m coming out of the sun! I’m black enough as it is », « Put on your sun cream; you don’t want to become black like me! »… are no strangers to this story. Deconstructing a model that has forged societies takes time; by starting to work for ourselves, we help to better understand what colorism has implied and still implies in our lives, to try to detach ourselves from it and not reproduce its biases, to learn to have consideration and love for our bodies, for our beings.

(*) I highly recommend reading this short work, which is truly instructive for understanding our Caribbean societies. However, it is a scientific essay, the language register is sustained, and the specialized vocabulary can make it a slow read (understand that you will sometimes have to reread certain sentences and consult a dictionary from time to time if – like me – you don’t remember or don’t know the meaning of entomologist, isomorph, apriorism, matrix ontology…).

All articles of the series Colorism and life opportunities during Slavery

#1 Skin color and mixed race in the 18th century

#2 Differentiated access to freedom

#3 Inequality of opportunities at work

#4 Values tainted by prejudice

#5 The imbalance in relations

#6 Capital disparity

French Bibliography

- Pierre-Louis, Jessica. Les Libres de couleur face au préjugé : franchir la barrière de couleur à la Martinique aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, thèse de doctorat d’Histoire, AIHP-GEODE EA 929, juin 2015 à l’U.A.G

- Pérotin-Dumon, Anne. La ville aux îles, la ville dans l’île: Basse-Terre et Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, 1650-1820. Paris: Karthala, 2001.

- Sainton, Jean-Pierre. Couleur et société en contexte post-esclavagiste: la Guadeloupe à la fin du XIXe siècle. Pointe-à-Pitre: Jasor, 2009.

Archives

- Manioc

la base de données « Esclavage en Martinique ».

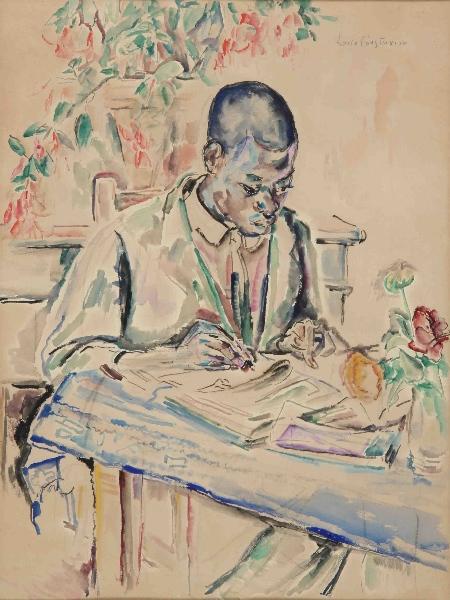

Iconography

- Joconde

Cousturier Lucie, « Le Nègre écrivant« , 1936, M0941000079.