Reading time: Around 18 minutes.

–> Lire la version française de cet article ![]()

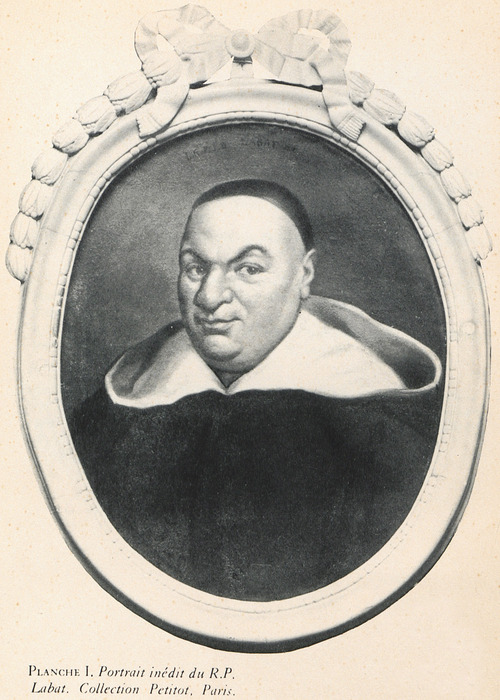

Father Labat, a religious chronicler, gourmet and gourmand, even glutton

Among the well-known figures in the history of French colonization, Father Jean-Baptiste Labat is a name that cannot be ignored. He provides a wealth of information from his experience in the islands between 1694 and 1705. What struck me in Father Labat’s accounts was his immoderate interest in food. Not only does he describe the plants and animals, but he is also interested in the different ways of preparing fruits, vegetables and meats in the islands. He tastes everything, even the fried worms of the palm trees. He is a fan of smoked turtle meat. He raves about the « so good » preparations based on sweet fruits, he is obviously familiar with recipes for fermented drinks… The man is a gourmet and a gourmand, not to say a glutton or a greedy person! He is a true culinary critic who delivers « ways of cooking », in other words, recipes that do not yet bear the name and that contribute to our gastronomic heritage. So I decided to start a long series to talk about gourmandize, grub, chow, festing, cooking, eating and feeding in the Caribbean from his prolix writings!

To learn more about this Dominican missionary and his book Nouveau Voyage aux isles de l’Amérique, I invite you to read the first post in the series on food and fasting (with a recipe for roasted devil). Today, I propose to see the recipes for hot chocolate, a drink so popular in the Carribean.

Cocoa: type, origin and distribution

Cocoa is one of the major foods « discovered » by Europeans with the colonial conquest of the Americas. Cultivated, transformed and consumed by the Amerindians in the form of beverages often enhanced with chili pepper, cocoa spread to Spain at the end of the 16th century and chocolate became an essential beverage in Europe over time, this time accompanied by sugar.

In the Americas, cocoa was consumed by the Olmecs, the Mayas, the Aztecs… It was drunk in the form of chocolate, offered as a gift, and was also used as currency in the form of seeds. The pods contain about thirty seeds surrounded by a pulpy white flesh and sweet in the mouth that is fermented. They are then cleaned and roasted to develop the aromas that make the drink so special. Then they are crushed to form a paste which, diluted with a liquid, gives the beverage. Depending on the circumstances and the desired use, the Amerindians added chili pepper, achiote, corn, fruits, and sometimes even hallucinogenic mushrooms.* It was the removal of the chili pepper in favor of sugar that ensured its success with the Europeans.

Tacking chocolate

« I have always used the term take chocolate, when I speak of the action that one does by feeding on it, because it is the most appropriate and significant to express this action, because one cannot say drink chocolate, as one says drink water and wine; one cannot also say eat chocolate, when it is dissolved in some liquor. It is too thick to be drunk, and too clear to be eaten; just as one does not say to drink a broth, or a medicine. These reasons seem to me sufficient to authorize the use of saying, to take and not to drink chocolate. « (T. 2 p. 376/421)

This reflection by Labat is in line with the questions I had already raised in the first episode of this series about the nature of the « beverage of the Gods ». Indeed, for Labat, chocolate was not consumable in times of fasting; he based himself for that « on the opinion of the Spanish doctors, who agree that there is more nourishing substance in an ounce of chocolate than in half a pound of beef; and on this principle, I maintained that one could not take it without breaking the fast, even if we just do it with water like the Spanish do. » (T. 1 p. 59/89)

We understand that for Labat, it was a rich food which, if it could not be eaten like a solid food, could not be considered either with the equal of a liquid such as coffee or tea, because of its composition. Indeed, chocolate is composed of a cocoa paste, a solid material that is diluted in a liquid to make the much appreciated beverage.

Chocolate, hot or cold… or tempered?

Just as he was interested in the richness of the food to know if it could be consumed in times of fasting, Labat also questioned its nature. At the time, foods were classified « on scales ranging from hot to cold and from wet to dry, in accordance with the theory of humours ». Labat thus expressed the divergent opinions on the subject.

Mr. Cailus, French, thought that it was a temperate food. But the Spaniards considered cocoa as cold and dry… »Who of all these authors is right? One will judge it on what I am going to say. It cannot be denied that Cocoa is oily and bitter, and everything that is oily and bitter is hot (…) The Spaniards easily justify the universal practice they have of mixing a quantity of very hot ingredients with Cocoa; they believe it to be very cold (…) on this principle they are right to consider it as a hot food. ) on this principle they are right to mix with Cocoa a considerable quantity of cinnamon, sugar, chili or pepper, or seeds of India wood, cloves, amber of musk, & especially vanilla, very hot ingredients, as everyone agreed: because to take a very cold thing without these powerful corrective agents would be to expose oneself to great inconveniences, & perhaps to a premature death. » (T. 2 p. 364/408) Labat notes that wherever chocolate was consumed, food considered as hot was added and that despite everything the drink produced many good effects on the organism: for him, it was thus that the combinations made it possible to obtain a tempered drink, which could be possible, according to the logic of the time, only if the cocoa was indeed cold.

In any case, being interested in a possible virtue of chocolate, Labat notes that chocolate makes you hot; which you will probably have also experienced when consuming any beverage or any generously spiced dish! « The Spaniards, and in imitation of them many other nations, make « soldiers », or small slices of roasted common bread, or cookie made on purpose, which they dip in their chocolate, and eat before taking it. This method cannot be bad, on the whole, if it is true, as they claim, that phlegm, crudeness and other impurities which are in the stomach, attach themselves to this bread, and that the chocolate finding them there assembled, consumes them, or precipitates them more easily, which is no small virtue in chocolate. It is good to rest for a few moments after it is taken, because it excites a little sweat, or wetness which opens the pores, and makes the bad or useless humors sweat. » (T. 2 p. 377/421)

An everyday drink taken by everyone, everywhere and at all times!

Wherever he went, Labat was always invited to drink a bit of chocolate, on land as well as at sea, with the French, as well as the English and the Spanish; Labat drank chocolate in Martinique, Hispaniola, St. Croix and Barbados.

Thus, on Monday, February 1, 1694, Father Chavagnac took Labat to get chocolate from one of their neighbors, called Mr. Bragus. Later, Labat took some chocolate that Mr. Dauville had had prepared for him. (T. 1 p. 50/80) When he went to Mr. Poquet’s house after the mass, where he was invited with others, « most of them did not leave to take chocolate« . (T. 1 p. 59/89) When he went to see Mr. Houdin who had his house in town, there again the latter made him take chocolate, & asked Labat to come to dine at his place. (T. 1 p. 66/98) Another time, Labat went to say the mass to the Capuchins, & took once again the chocolate at Mr. Houdin. (T. 1 p. 36/258)

While on a trip to Barbados, Labat visited the minister of Spiketon and left at eight o’clock, after having taken chocolate milk. (T. 2 p. 132/160) Later, on a trip to St. Thomas/St. Croix, Labat wrote that he took chocolate before going for a walk in the town to the Comptoir and, further on, that the English ladies who received him had the chocolate prepared. (T. 2 p. 287/327 & p. 492/544)

In short, chocolate seems to have been an essential part of the colonial world in the art of receiving a visitor throughout the Caribbean. The beverage was consumed by the Amerindians, as well as by the white Creoles and free people of color, by young and old alike, whether as a snack or as part of the meal, in the morning at breakfast, before dinner in the middle of the day, in the afternoon or at supper to round off the meal, or even on its own as a light meal at night.

Mentioning the cocoa trees cultivated in the Fonds Nègres district in Hispaniola by free people of color, Labat tells that the children of the place were fed in the morning with a chocolate drink made from corn. (T. 2 p. 262/300) Labat had for his part the habit of consuming it in the morning. (T. 1 p. 53/83) The enslaved man who accompanied him on his travels also drank it, although I do not know if this practice was common for enslaved people. (T. 2 p. 128/154)

Even when he was stopped by a Spanish ship, Labat was served chocolate. He describes the service on board as including « jams, cookie, and wine & then chocolate, which was very good. » (T. 2 p. 272/312) Chocolate was also sometimes taken while waiting for dinner and Labat specifies that for the evening « Usually only one meal was served, most of them only took jams and chocolate in the evening. But while we were stopped, a very honest supper was served for M. des Fortes and for me« . (T. 2 p. 275/315)

Hot chocolate, the art of variations.

The cocoa paste

Labat basically refers to two techniques for making cocoa paste. The base is the same. The cocoa seeds were collected, put to dry, the skin was removed, they were roasted more or less strongly and then they were crushed until a paste was obtained. One of the differences lies mainly in the fact of crushing the seeds alone (French way of doing according to Labat) or by adding the spices (Spanish way of doing). (T. 2 p. 366/410)

The liquid

When I think of hot chocolate I spontaneously think of the milk it contains. But it is not always this liquid that is preferred for the realization of the drink, especially in Labat’s time. « The most ordinary and natural liquor to dissolve chocolate is water. There are people who use milk instead of water. When milk is used alone, it makes the chocolate too thick, too nourishing and more difficult to digest (…) This is not the case when it is made with one third of milk and two thirds or three quarters of water. This little milk helps to make it foam and to make it very delicate. » (T. 2 p. 372/416)

Labat also notes the use of a kind of vegetable milk made from corn (called atole) which he finds used by the Spaniards and by the free people of color in Santo Domingo. (T. 2 p. 366/410 & p. 370/414) Finally, he notes sarcastically that « The English of the Isles often make it with Madeira wine; I tasted it once in this way out of pure curiosity, and was so pleased with it that the desire never returned to me to make a second trial. » (T. 2 p. 372/416)

Spices in quantity

The considerable quantities of « cinnamon, sugar, chili or pepper, or seeds of India wood, cloves, amber of musk, & especially vanilla » that Labat lists in Spanish chocolate were not peculiar to that nation. Everywhere, chocolate seems to have been embellished in different proportions with various spices. « It is said that the Spaniards at the encouragement of the Indians put achiotte, otherwise roucou, in their chocolate to give it a red color. I doubt that this is the case, unless they mix this color as they want to use it: for I have seen many times chocolate from the new Spain, which was certainly not red, but black. » (T. 2 p. 370/414)

Cooking on the fire or in a bain-marie

« There are people who, instead of putting the chocolate on the fire, put it in a bain-marie, claiming that this makes the chocolate more delicate; I have taken some several times in this way without having found any noticeable difference from that which had been made simply on the fire. The only thing to avoid is that it smells of smoke. » (T. 2 p. 374/418)

The accompaniment: bread cookies or cassava

As seen above, « The Spaniards, and in imitation of them many other nations, make « soldiers », or small slices of roasted common bread, or cookie made on purpose, which they dip in their chocolate, and which they eat before taking it » (T. 2 p. 377/421). « (T. 2 p. 377/421) Labat describing the kitchen service on the Spanish ship also expresses his surprise: « I found it a little strange at first that almost all those who were at the table ate cassava rather than cookie, although it was very white, very light, and very well-made ». (T. 2 p. 274/314) It is thus a long-standing custom to accompany chocolate with a « cookie » which is now traditionally a type of Zpof [pain au beurre] in Martinique.

Father Labat’s chocolate recipe

Let’s get down to the serious stuff (at least for those who like to test their cooking), the recipe! Here is what Labat recommends:

« Supposing, therefore, that one wants to make eight cups of chocolate of a reasonable size, one puts a pint of water on the fire in a vessel such as it can be, in order to boil it, & one puts in the chocolate pot two ounces of cocoa paste ground into powder, with three ounces of sugar, & up to four ounces when the paste is recent & consequently more oily &; more bitter. A fresh white and yellow egg is added, along with a little cold or hot water, which is not important; cinnamon powder is sifted through a silk sieve as much as can be contained in a liard, and if you want the cinnamon to have a more pungent and stronger taste, twelve cloves are crushed into two ounces of cinnamon to make up the powder I just mentioned. The paste, sugar and cinnamon are mixed as much as possible with the egg and the little water that has been added: When the water is boiling, it is poured little by little into the chocolate pot, and the matter is shaken strongly with the whisk [moulinet], not only to separate and dissolve the parts of the cocoa and sugar, but mainly to make it foam; when all the water is in the chocolate pot, and the whisk has been well used, it is put on the fire, or left until the foam is ready to pass over it. We then remove it, and make the whisk work strongly, so that this foam, which is the most oily part of the cocoa, spreads well throughout the liquor and makes it equally good at the end as at the beginning. The chocolate pot is put back on the fire, and care is taken to use the whisk when the matter comes to a boil and wants to rise above the pot; it is left to boil a few times to give it a reasonable cooking time, and it is removed from the fire; the whisk is then used, and as the foam accumulates at the top, it is gently poured into the cups with the help of the small round plate that is above the apple. The material is thus agitated to reduce it all to foam, at least as much as possible, and then the little liquor that remains in the chocolate pot is divided among all the cups. » (T. 2 p. 373/417)

« When you want to put a third or a quarter of milk with the water, it is not necessary to put an egg in it, nor to boil the water & milk before putting them in the chocolate pot, it is enough that the water is quite hot; you do the rest as I have just marked it. » (T. 2 p. 374/418)

Labat’s recipe adapted

To begin, I went to the market to buy a stick of cocoa (or gwo kako), which seems to me to be the closest thing to chocolate at that time; for the same reasons, I preferred whole milk to semi-skimmed. Then, I took the opportunity to buy a nice vanilla bean, since Labat does not specify its shape for the second recipe.

As for the measurements, I made the conversions: a pint of water was about 476 ml of liquid, 1 ounce was about 28 g, 1 liard was a small coin that fits on a fingertip. I rounded up for the practicality of making it in the kitchen. For the material, I don’t have a chocolate maker nor a moulinet. But I do have a good pan and a modern whisk. Well, that does the trick. For this first recipe, I tested the water and egg version.

Ingredients

- 500 ml of water

- 60 g chocolate

- 90 g sugar (see the advice section!)

- 1 egg

- 1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

Coarsely grate the chocolate into a large bowl, add the sugar, cinnamon and egg. Take a little water from the 500 ml and add it to the previous ingredients and mix well. Bring the remaining water to a boil. Gradually add the boiled water to your chocolate mixture. Mix well with a whisk. Put the mixture back in the pan on the heat. Let it form a few bubbles that will thicken the whole and beat again with the whisk.

Serve and enjoy.

The technical gesture that changes everything: foaming the chocolate!

Frankly, I was really satisfied with my business, until I reread all my notes from the book: « There are people who neglect to make chocolate foam, & who imagine that it is enough that the paste is well diluted in the liquor, and that it has made it thick. I could not compare these kinds of people better than to those who make no difference between a light and well risen bread and a heavy and badly made one. Yet it will be the same flour, in the same quantity, but worked by two different workers, one skilled and diligent, the other ignorant and lazy. » (T. 2 p. 371/415)

…

Did I feel ashamed and do it again, managing to: « as the foam collects at the top, it is gently dropped into the cups with the little round plate that is above the apple. The material is thus agitated to reduce it to foam, at least as much as possible, and then the little liquor that remains in the chocolate pot is divided among all the cups »? (T. 2 p. 374/418)

Yes.

Since I still don’t have a chocolate pot with a small round plate, I used a serving spoon. To tell the truth, I then tried using a milk frother, but since the recipe doesn’t have milk, in both cases it was not very conclusive. I persisted with the third cashew recipe, this time with a liquid base of water and milk, but if you leave it more than a few broths you get more of a cream than a drink; the frother can’t do anything with that thickness. So, in my opinion, if you absolutely want foam, make a milk foam on the side and add it to the cup.

The recipe for Spanish chocolate

For the second recipe, I relied on what Labat explains about the cocoa paste made by the Spaniards and Italians: « To make one hundred pounds of the finest & best chocolate, one takes forty pounds of cocoa paste well worked on the stone, one even sixty pounds of sugar very white, very dry, well crushed, two pounds of cinnamon, four ounces of clove, & eighteen ounces of vanilla crushed together in the quantity of musk and essence of amber that one judges appropriate (…). When one wants to use this chocolate, one puts in the chocolate pot as many cups of water as one wants to make cups of chocolate; and when this water has boiled for a few moments, one throws in as many ounces of chocolate as there are cups of water. One stirs strongly with the reel to dissolve the matter, and one puts the chocolate pot back on the fire to make it take a few boils; one stirs again with the reel, in order to make the chocolate rise in foam, and one thus fills the cups little by little. It cannot be said that chocolate made in this way is not extremely flattering to the taste and smell. » (T. 2 p. 368/412)

Using the given proportions, I reduced it so that I could make the same amount of beverage as in the first recipe. I did not mix my sugar and spices with my cocoa paste to make a stick, but simply mixed them together as in the first recipe. I obviously didn’t use musk or amber. And this time, I chose to use 2/3 water to 1/3 milk, without egg.

The Spanish recipe adapted

Ingredients

- 500 ml of liquid (2/3 water, 1/3 milk)

- 60 g chocolate

- 90 g sugar (see the advice section!)

- 2 g of cinnamon

- 2 g vanilla

- 4-5 cloves (which I did not grind!)

Coarsely grate the chocolate into a large bowl, add the sugar and spices. Take some of the 500 ml of liquid to add to the previous ingredients and mix well. Put the mixture and the rest of the liquid in a saucepan on the heat. Mix well with a whisk. Allow to form a few bubbles that will thicken the mixture and beat again with the whisk.

Serve and enjoy.

The recipe for cashew chocolate

Finally I did not test a version with corn milk, on the other hand I tried to realize a recipe corresponding to Labat’s experience with cashew nuts: « I took chocolate in which there was half Cacao & half cashew nuts. I will explain below what this fruit is. In the meantime, I will say that this chocolate was very good, that it foamed wonderfully, and that it retained the taste of the cashew nut which is very pleasant. « (T. 2 p. 380/424) Faced with the lack of information, I took a lot of liberty in trying to be inspired by the previous proportions.

Ingredients

- 500 ml of liquid (2/3 water, 1/3 milk)

- 60 g chocolate

- 60 g cashew nut puree

- 20 g sugar (see the advice section!)

Coarsely grate the chocolate into a large bowl, add the sugar and cashew puree. Take some of the 500 ml of liquid to add to the previous ingredients and mix well. Put the mixture and the rest of the liquid in a saucepan on the heat. Mix well with a whisk. Allow to form a few bubbles that will thicken the mixture and beat again with the whisk.

Serve and enjoy.

Tasting and personal opinion

We were two foodies at the tasting, Superincognito and me. What marked us was the good smell of the first two versions and the quantity of sugar! 90 g of sugar for 1/2 liter of drink! I understand that this half-liter was intended for 8 cups per Labat; but according to our current tastes, I think you can easily divide the sugar dose by two.

I have a soft spot for the first recipe, besides its interest for my lactose intolerance, it also keeps more of the characteristic smell and taste of the roasted cocoa bean. We love it! The egg brings a creamy and smooth side. Superincognito was surprised by this thick texture that he did not think he could obtain with water; and he was also marked by the more present aroma of chocolate. However, the texture of the drink is less bound than when using milk as in the second recipe. For this second recipe, it was the presence of the spices in the mouth that we liked, the clove gives a power to the drink that the cinnamon does not bring alone. We think that a touch of chili would have worked wonders. Superincognito pointed out the more liquid aspect of this second version and the less present taste of chocolate. But he insists that both recipes are delicious.

For the third recipe, I opted to put sugar according to my taste, so very little, it doesn’t make everyone happy. The mixture thickens up a lot from the first boils, if you like a very thick texture, close to a cream dessert, it can be really nice even cold, but if not, skip it or make sure to stop cooking before it thickens. The presence of the cashew nut remains very subtle, in the absence of spices it is the full-bodied flavor of the chocolate that is fully expressed.

To consume with moderation!

I could not conclude better than Labat: « I have one more warning to give concerning chocolate, which is to use it with moderation, however good and well-conditioned it may be, because the best things become bad when taken in excess. » (T. 2 p. 387/433)

And you, how do you make your hot chocolate? Water or milk, egg or not? Which spices do you prefer to use? Test these historical recipes, make your own adaptations and share them with us!

Bibliography

- *Flandrin, Jean et Montanari, Massimo, Histoire de l’alimentation, Paris, Fayard, 1996.

Archives

Iconography

- Base de donnée Manioc PLANCHE I. Portrait inédit du R.P, Labat. Collection Petitot, Paris. Extrait de : Voyages aux Isles de l’Amérique (Antilles) 1693-1705. Tome 1.

- Base de données La Joconde, Nature morte au bol de chocolat par Juan de ZURBARAN vers 1640, peinture à l’huile sur toile